Making Sessions Run Better

Bottom of Form

Tips for Making Sessions Run Better

Once you understand the basics of neurofeedback, including how to get good connections, open a design, and run a session, you are likely to have more nuanced questions. This section is intended to help you get some of the neurofeedback training answers you need to become a seasoned brain trainer.

(INSERT LINKS FOR THIS LIST TO WHERE THEY APPEAR IN THE TEXT BELOW)

Abreactions

Artifact

Blinking Eyes

Contraindications for Training

Cultural Differences

Eyes Open vs Eyes Closed Training

Falling Asleep During Sessions

Feedback

Four-Channel or More Training

Frequency of Training

Gender-Related Differences

Handedness and Training

Headphones

Hemispheric Dominance

Linking Training Sites

Muscle Tension

Session Timing and Length

Skull Thickness

Reactions to Training

Training Specific Bands

Abreactions

Abreactions are any unwanted and usually negative responses to brain training. They are rare when one is carefully following a brain map, and no research has ever found that there are lasting negative effects to a few sessions with negative reactions. That said, there is usually never a time when a negative response such as headache, spaciness or extreme exhaustion is something we should work through. I would admit that there are times when a client may have a slight headache after or during a session but the next day experience a dramatic change. In that case I might (with the client’s agreement) try it again, but ideally I’d want to know what about the protocol was resulting in the headache or the extreme exhaustion. There is no reason for a Calvinist approach to neurofeedback.

Artifact

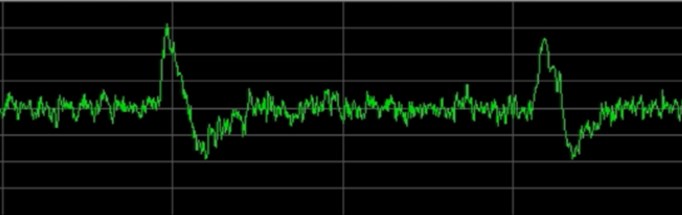

If you watch the oscilloscope, you’ll get comfortable reading what EEG activity looks like: it is not generally repetitive or overly consistent. When all the wave forms are roughly the same height, instead of taller and shorter, that’s probably not brain. If the width of the waves are very consistent rather than shifting to wider (slower) and narrower (faster) patterns, again, that’s probably something mechanical rather than organic. Sudden spikes, especially when they are repetitive, probably also indicate a problem.

Artifact in Assessments

Artifacting can make a big difference when the artifact is strong. Watching for artifact when you replay a session, you can get a pretty clear picture of what it looks like on the Power Spectrum and/or Oscilloscope displays. Then you can recognize it on the screen during the assessment data gathering. That’s the ideal time. The more you can avoid artifact in the recording, the easier it is to remove it in the processing. You’ll end up with more seconds of clean data and spend less time getting it.

Do not assume that auto artifacting will “skim off” the high amplitudes. In a well-recorded assessment, the auto-artifacting frequently removes zero segments as artifact.

About my 2nd year of working with clients, Joel Lubar was kind of a mentor to me. He had come to visit us in Atlanta one time, and we had just gotten an artifacting version of what was called A620 software. You looked at two-second epochs as raw waveforms and either approved or rejected them based on the one channel of data. I had just gotten the software and begun working with it, so I was artifacting a file while Joel sat beside me at the computer. Joel was not one to suffer in silence, so after a few sighs watching me stare and stare at a 2-second epoch, he stood up to go out and get something from the car or something like that. As he left, he turned back to me at said, “try something for me.” He asked me to continue artifacting this 2 minute file as carefully as I possibly could and save the results. Then do it again as fast as I could, just removing the most obvious artifacts. “See how different they are,” he said and left for about 20 minutes. By the time he got back, I had gotten the message. Big, obvious artifacts are the ones that really mess up the averages and standard deviations of the data. The ones so small that you can’t really be sure they are or aren’t make almost no difference at all.

Eye Artifact

An eyeblink lasts 1-2 seconds in its effect on the EEG unless you are blinking very rapidly. Eye movement, cable movement and eyeblinks are all slowwave excursions, so they will appear in the power spectrum and oscilloscope.

An eyeblink lasts 1-2 seconds in its effect on the EEG unless you are blinking very rapidly. Eye movement, cable movement and eyeblinks are all slowwave excursions, so they will appear in the power spectrum and oscilloscope.

Teach your clients to “peek through their eyelashes” when training frontally. I tell them, “pretend you’re in a room full of adults and you REALLY want to stay to see what’s going on, but you know they’ll make you leave if they think you are awake. So you pretend your eyes are closed, but you open them just enough to be able to see.”

Each eye has a voltage drop in the eyeball. Even being close to the eyes can cause an effect on the signal.

Eyes moving, even with eyes closed, will cause delta artifact the further forward the electrodes are.

You can and do blink and move your eyes when they are closed. Try it and you’ll see the effect on readings taken in the frontal areas. Regularity of the surges would suggest blinks.

I look at the power spectrum in bins mode. If all the frequencies on both sides surge out and then come back pretty much together, that’s almost certainly eye artifact. If the high amplitude activity appears in various frequencies and moves around in a more organic way, then it’s probably brain.

If you are consistently seeing high levels of delta (recognizing that delta is often the highest power in many brains except for posterior eyes closed alpha), I would always check the eyes. Eye movement, electrode movement, eyeblinks and even the eyes themselves can produce high levels of delta. And, of course, if you did not artifact the data before dumping it into the assessment, it’s pretty worthless. I work with dozens of trainers at any given point in time–include rookie home trainers just starting out–and see nearly all of them able to get useful assessments if the data are carefully gathered and properly artifacted.

Eye rolls also create artifact that appears as excessive slow activity. You can see them as the whole wave form rolls up off the baseline and then down below it.

Contact lenses tend to magnify blink artifact significantly.

Muscle Artifact

Any muscle tensing or bracing produces a surge in most frequencies, but especially in the higher bands (like high-beta). EMG is usually seen between 50 and 200 Hz, but, depending on the amplifier being used, the EMG may not appear at all, because the amplifier only reads up to 35-45 Hz. Nevertheless, high-beta (and often fastwave coherence as well) will appear very high when it is in fact an artifact of EMG.

EMG is usually defined as 20-200 Hz, though obviously there are lots of EEG signals in that range as well. If you grit your teeth while recording EEG, you’ll see a surge in nearly all frequencies, but the higher the frequency the greater the artifact. Since most amplifiers have lowpass filters built into them to cut off very high frequencies like this, depending on what amp you are using, you may be thinking you are training a frequency your amplifier can’t even see.

Oz is generally about 1.5 inches above the inion. That’s still pretty close to the neck muscles. Be very careful to have the client sit with head up, not dropped forward, to avoid producing muscle artifact from those muscles. This is an issue we talk about in the assessment process, especially for the Midline reading and especially at task.

Artifact in the Signal

Lots more 60 Hz signal when it is by itself is often a measure of quality of hookup. When it is very high relative to the rest of the power spectrum, it’s almost always an issue of poor impedances/bad scalp connections.

If levels of 60 Hz are within the range of the other amplitudes in the EEG and you don’t have impedance problems, it’s not a big thing. Remember that we don’t actually measure anything anywhere near there with the filters in the assessment or training designs. What you need to watch for is usually clear in the power spectrum. If you see regular spikes up and down the EEG (for example, at 22, 35, and 50 Hz), that is a seriously bad signal.

Heartbeat Artifact

Regular pulses, depending on their frequency, can often be related to artifact, especially ECG. Especially with clients who are heavy. You may be picking up pulsing in a blood vessel. It’s not common to see any kind of regular oscillation that affects all frequencies repeatedly. And since such an artifact would be expected to result in activity at all sites coming from the same source (the artifact), that would be a rule-out in a case where coherences were generally high.

If someone is producing ECG artifact, you can see the regular pulsing in the oscilloscope. Usually earlobes are a major culprit, so I move from the ears to mastoids or use a bipolar montage. Occasionally I have managed to get a head lead directly over a blood vessel under the scalp and moving the offending electrode will fix the problem.

I don’t recall having personally run into a client where we couldn’t get away from the pulse. I’d be hesitant to try to set up a filter in the specific frequency where the pulse occurs to filter it out, but that’s possible. Heart rates usually run from, say, 50-90 pulses per minute, which would be from around 0.8 to 1.5 Hz. (If your heart rate is 60 bpm, that would be 1 Hz–60 in a minute divided by 60 seconds.) Putting a filter down there with a threshold that blocks sudden amplitude surges would at least block the signal at those times.

You can actually move earclips up to the cartilage area closer to the top of the ears. The problem with ECG is almost always in the earlobes, and moving to the mastoid or the cartilage almost always helps.

Electro-magnetic Fields

These can be caused by ungrounded laptops, power supplies, or almost any electrical equipment–sometimes equipment you can’t even identify. These often appear as high coherences in faster frequencies and high levels of fast activity.

Ungrounded laptops are a significant source of artifact. If you are using a 2-prong plug instead of a three-prong plug, even in a grounded outlet, you won’t get the benefit of the grounding, and you are likely to have a noisy signal. Try unplugging the AC adaptor from the wall and the computer while you are running and see if the signal cleans up.

Watch for coherence levels being artificially high if you have significant electromagnetic field interference. Even if you use your notch filter and keep the training range to 1-40, coherences can be adversely affected.

Electrodes that are scratched, have nicked wires or are long and stretched out creating an antenna to pick up signals also are a source of artifact.

I’ve certainly seen cases of intrusive EMF: in Zurich I did a workshop with one of their electric trolley lines outside the building and we all (using cabled amplifiers) had such horrible noise problems that we had to drop the part of the workshop related to gathering assessments. In Sao Paulo, trainers I consult with have struggled with such problems due to their proximity to a broadcasting tower. In California I was called to an office to figure out why it was impossible to get a decent signal in one room, when signals were fine on both sides and downstairs from the same office. None of us three “experts” who were there were able to find the source of the problem. All of those cases involved cabled amps. But those were very rare experiences among the thousands of situations I’ve seen and trained in.

Assessing and Training the Pre-Frontal Cortex

Fp1 and Fp2 are extremely difficult sites to evaluate and to train, because they are extremely close to the eye muscles (blink or eye movement cause excessive slow frequency artifact) and they are right over all those expressive muscles in the forehead. It is almost impossible, except with the most controlled and motivated client, to get a decent artifact-free reading there.

Blinking

Blinking is very interesting. We used to use it as an indicator of progress in speeding up the brain. When a client was holding down theta relative to beta, blinking frequency dropped way down. This was very reliable.

People who have a fair amount of slow activity OFTEN blink a LOT! Don’t know why that is, but it’s a commonly–if anecdotally–recognized finding. And as you speed up brain frequencies, commonly blinking becomes less of an issue.

Contraindications for Training

I don’t think of anything that would be contra-indicated for brain training if you are willing to take on the person/support system that carries the brain around. We screened out families with split parents (one strongly favoring training, the other strongly opposed) and kids on three or more psychoactive meds. We worked with things that I didn’t think had much of a chance of responding, telling the client that up front and letting them choose to take the flier (e.g. a guy who was losing his sight, people with active Alzheimer’s). Maybe the main contra-indication would be for clients: don’t work with careless trainers who don’t know what they are doing. That is the largest group of “damaged” people I see. You might also want to stay away from shoppers with absolutely mind-boggling stories who have tried a dozen other things, none of which worked or which made them worse. I still might try if I were intrigued by the person, but I’d go into it knowing that our chances were pretty slim.

Perhaps a corollary to the question is, “are there things you don’t think NF can help with?” My answer would be yes, though I know there are folks on the group who will disagree with each of these, and if they are truly helping clients get results with those issues, then I hope they’ll enlighten me. I don’t train active Alzheimer’s, because I’ve tried several times and gotten absolutely no results trying everything I could think of or others had claimed efficacy for. The folks who tell me they are getting results say, “I think we are slowing the rate of decline.” If everyone agrees with that, then great. I just have no idea how one measures that, and I haven’t seen anything I could seriously propose for that in my own experience. I use a simple rule. If it were ME who was paying for this training, would I keep spending the money. I wouldn’t if I had a family member with active Alzheimer’s. I’ve had no success in working with very low IQ children. Not that we couldn’t train them; just couldn’t get any lasting effects we could notice. Broken bones or nerve transmission issues or tumors or other physically-based issues aren’t likely to be helped much by NF. But anything that has a connection to the brain and its efforts can probably be impacted by a knowledgeable trainer.

I don’t think of contra-indications as the same as side-effects. Side-effects are signposts (as much as positive outcomes) that guide the trainer (if he/she happens to be paying attention) in steering the training. We can certainly make folks more tuned in to certain of them (nobody ever told me about beta and itching, but now that I know about it, I keep a careful eye out for it). And we can try to steer people away from certain kinds of things that are more likely to trigger them.

I think of contra-indications as elements in the assessment that would say, “don’t do NF with this client”. You don’t give medications to a person who is allergic to them. That’s contra-indicated. Other than the ones I mentioned (parental splits and heavy medication) there really aren’t any that I can think of in my own work.

Pregnancy and Neurofeedback

I don’t know any reason why making a prospective mother calmer, happier, more focused, better centered or whatever would have anything but the most positive effect on her (during a stressful period) or her child. Just make sure to increase your prices (training two for one!).

Seizures and HEG

I don’t think there’s any reason not to do LIFE HEG. Seizures are generally related to lesions in specific areas of the cortex–generally not the prefrontal. They are the result, simplifying a bit, of a very slow brain area which slides down toward sleep and results in an idiosyncratic response where the brain bursts into very fast activity to wake up. If that move results in kindling of the beta–so it spreads across neuron pools in a highly coherent way–you get a seizure.

Improving function in the PFC should, if anything, improve control, not reduce it.

Cultural Differences

I agree that it’s likely there are cultural differences in brains. Heck, there are large individual differences in their patterns, why not cultural. I don’t think I ever did an assessment in Switzerland or Korea that didn’t have hot temporals, but no one ever indicated an interest in training to reduce anxiety. High levels of fast wave activity were common in those (and other) places. I trained hot temporals and trainees found the changes pleasant in Switzerland. The Koreans were so polite that they really wouldn’t say much about what they felt before or after the training. There is no question that cultural issues are involved in training. I’d love to see if they are also somehow related to changes in macro brain organization, which is what the T looks for.

Eyes Open vs Eyes Closed Training

As for training down beta and high beta, in my experience it matters quite a bit whether you are training eyes closed or eyes open. Also what kind of feedback you are giving can make a difference. Using contingent feedback (beeps or clicks) only when the client passes on all filters can result in a highly beta-oriented person “trying,” which often will increase fast activity. I often use eyes-closed protocols with musical (continuous) feedback, so the client never “passes” or “fails”. Since the music is slow and relaxing, and there is not visual feedback, the brain can relax and let go the beta.

When a client has significant fast temporal activity with eyes closed which drops off when eyes are opened, does it make sense to train it eyes-open? If that is a hypervigilance response from the amygdala to the experience of being cut off from warning signs (can’t see danger), then teaching the brain to let it go a little at a time can have a remarkable effect. I’m even doing some EC theta/beta ratio down-training with eyes closed. It’s a lot easier in the frontals that way and rarely do clients complain of being sleepy or tired after a session.

Bottom-line: it ain’t that complicated. You ask the client to keep his/her eyes closed, put on some headphones, find a sound environment the client likes and start the program. Many of my clients are adults, and they invariably ask, “what am I supposed to do?” I tell them, “It’s just music. Just listen to it. You don’t have to worry about it. But when you hear the bell, know that’s really good.” Of course, being adults and knowing that nothing is ever that simple, they spend a few minutes (sometimes longer) trying to figure out, “when I did this, did the sound go up or down?” But eventually they are seduced by the music, and they truly can’t figure out “how” they’re doing it, so they just stop trying and listen and the brain takes over from that noisy conscious mind. And they get better. Best of all, it’s not uncommon for folks to come back up after 20 minutes and say, “I really liked that music; can I get a copy of it?” They cannot believe their brain was the artist.

Falling Asleep During Sessions

You can work with a “sleeping” client with any EEG equipment. Unless you see a significant spike in Theta, the client is not really asleep. Letting a client “sleep” and get the brain into a solid SMR/sleep spindles state for a few sessions is very positive.

However, if in fact one has an unchangeable lifestyle that doesn’t allow one ANY down-time, no wonder he sleeps as soon as he has a chance to sit still for a few minutes! One of the questions an assessment would focus on is how effectively he is able to shift into neutral throughout the day when there isn’t any specific demand on his brain other than monitoring. Lots of clients with whom I work wear themselves out because their brains don’t know how to take micro breaks during the day.

Depending on the type of training one is doing, the appearance of being asleep does not stop the brain from receiving feedback signals and learning from them. But if someone is working with me and sleeps during sessions after the first 5 sessions or so, I suggest that one major goal of the training should be to learn the difference between being still and being asleep. Sometimes we have to do very short training segments–a minute or two–and pause to talk about what’s happening and how he feels. Then we can build up the training period from there.

Feedback

Don’t think; don’t try. Just pay attention to the feedback.

Meaning of Tones

What does music mean?!! What do sounds mean? Of course an anxious, obsessive person, a person driven by the need to control, wants to know that kind of stuff. That’s exactly why I started playing with music feedback when my son first introduced me to the WaveRider back in the mid-to-late 90’s. Of course, those clients HATED closing their eyes, and even more HATED being told just to listen. They resisted with every fiber of their conscious minds. But after a while they tended to wear themselves out and give up trying at least briefly–in short, to let the feedback actually pass through to the brain WITHOUT filtering the heck out of it with their minds–and to their horror it often had a positive effect.

When one is taught to believe that it’s really the conscious intellectual mind that has to make things happen, and when one commits to that belief, it’s incredibly limiting. I know that only those folks who live in their minds have figured out stuff like chaos theory and the various forms of “new” physics, etc. But I also know that the same stuff was known thousands of years ago by Taoist masters who had never heard of particle accelerators or quarks.

You can study music. You can use music. Or you can listen to it and resonate to it and enjoy it. If the conscious mind is indeed the one that runs the show, then we better explain the music–or better yet, just do away with it. If the conscious mind just gets in the way of much of life, then I feel justified in continuing to irritate the heck out of compulsive and anxious clients by refusing to talk with them about what the music means and what it’s “supposed to” do.

If your conscious mind really ran the show, then you would not be anxious, I tell them. You don’t want to be anxious. You’ve thought about it and tried to control it for years or decades. How come you are still anxious? Because the anxiety results from energy patterns in your brain, and you can’t “think” those away. Give up–or just keep being anxious and obsessive. Giving up control is the ultimate key to so much of life–the basis for meditation, religious experience, 12-step programs, getting into the zone, falling in love, and a lot of other important parts of experience.

How Feedback Works

One of the brain’s major functions/interests is to send something out (words/actions) into the universe and see what comes back. The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is selecting what to do and receiving the information back. I’ve used the analogy of a kid learning to wiggle his ears: if you can practice in front of a mirror that is immediate and accurate, you will learn much faster than if you just sit around and try to tell if you are doing it or not. The more you limit the brain’s experience to what is in the mirror (close your eyes, put on headphones, sit in a comfortable chair) the more clearly the mirror focuses the brain’s attention on a specific response. Combine that kind of mirror (we could call it “feedback”) with intention (e.g. I want to see my ears move in response to what I’m doing), and the brain can learn.

Take the WS Alpha temporal design. It changes the pitch and volume of the sound based on the amount of activity the brain is producing in the frequencies we want to reduce. Once the client stops “thinking” and “trying” then the brain is receiving feedback in the form of changing pitches and volumes, and as it looks through what it is doing it begins to recognize that there is a relationship between high energy states and the sound. That’s the feedback mirror. The intention is that I’ve told the client “you can’t MAKE the bell ring, but whenever it does, that is very good!” The brain can figure out that the chime rings only when it is moving to lower energy states, so it’s likely to move that direction. Sorry, there’s nothing magic about the tones or anything like that. They are reflecting brain activity, and we’ve given the brain a hint toward the desired direction.

So the idea of NF is that you set your thresholds so that the brain is rewarded for doing something it already does!! You teach a dog to sit by tossing him a treat each time he sits down on his own and repeating the command “sit.” If you take a client whose Theta/Beta ratio ranges from 1.8 to 5.0 and only give feedback when he hits below 1.5 (0% of the time), the brain will learn nothing. If you give the feedback whenever it is below 5.0 (100% of the time) it will learn nothing. But if you set your target at, say 3.8, so the ratio is below it 75% of the time, what happens. The brain is motivated to “cut off the outliers”–reduce the times that it goes way up in slow activity. This is done by improving control circuits. As they improve, eventually the brain’s “normal” range may change to 1.7 to 4.0, and you slide the threshold down to, say 2.9. Now a new batch of brain activation patterns are defined as “outliers” and the brain begins to learn to minimize them and further improve control. You are “shaping” the brain’s behavior, little by little.

Continuous vs. Contingent Feedback

Stripped of all the hype, there are two types of feedback: Continuous and Contingent. Continuous, which is heavily built into many of the brain-trainer designs, gives music or video feedback that doesn’t stop. It modulates brightness or pitch or volume or size to give the brain information. If you are reducing a type of activity we want you to reduce, the music may move to higher pitches and quieter volume. It’s no more complex than that. Your brain learns to connect the music moving in one direction with specific states it is producing, and we can guide it into new states.

This works fine with people who are “hyper” emotionally or intellectually–stressed, racing thoughts, anxious, etc. But if you take a person who is nearly asleep most of the time (ADHD or depressed) calming down is unlikely to help them.

Contingent feedback, with game interface or points, etc. keeps the brain engaged. When the brain starts to drift away, the feedback STOPS, so the client is pulled back. Clients needing to activate do better with Contingent feedback, where it is either on or off and only on when all training conditions are being met. Beeps and dings and clicks.

One of the things our designs try to do is to combine continuous feedback with contingent, so the brain not only can recognize the relationship between frequency activity and the music but can also recognize what direction is best to move in.

How to Coach Feedback

“Don’t think; don’t try. Just pay attention to the feedback.” The goal is to listen to the music. Pay attention to it and don’t worry about “trying” to make anything happen. When you try, your conscious mind gets between the feedback and the brain. When you just pay attention, let the music slide through the conscious mind, the brain gets the connection between what it is doing and what’s happening in the feedback.

Percent Feedback/Reward

I would define the feedback percent strictly in terms of the client. The more “internal” the person is, the lower reward rate I would set, trying to keep the client “out”. The higher the anxiety level, the higher the reward rate I would set, trying to keep the client from “trying” too much. I actually prefer to combine continuous and contingent feedback in a design, which allows me to set a more stringent target for the contingent feedback (which only plays when all targets are met), such as the 10% I use with the chime feedback in the Squish protocols, while giving the client’s brain continuous feedback that provides information via pitch and volume (or brightness of the video display).

I think most trainers would consider 40-50% to be pretty stringent as a reward rate and 85-95% to be pretty loose. On this list, a number of trainers have reported that they find that clients actually do better with the richer reward environments, and I have seen that in my own work with clients in a number of cases. Once again, for me it depends on the client’s response.

Delays in Feedback

To learn from feedback, the general rule is that it needs to be as immediate as possible. An analogy would say if you tried to learn to wiggle your ears by looking in a mirror, but you didn’t see the results of your actions until 10 seconds after you took them, the learning would be very slow. If you saw response immediately, the learning would happen more quickly.

I aim never to have the delay between activity at the electrode and feedback on the screen exceed 250ms. I think you may be confusing Sterman’s comments about re-charge period, the break between one bit of feedback and the next, with feedback latency.

MIDI

The sound of the MIDI object IS the feedback. There’s no “song” being played. Each brain in each session in each minute will play a different melody, because the melody is strictly based on what the brain is doing in the target frequencies.

Multiple Inhibits

I don’t often use multiple inhibit protocols. As soon as you start setting multiple reward/inhibit thresholds, you begin multiplying the problems in keeping all the targets set appropriately and losing control over the feedback rate. For example: If I have two inhibits and a reward, setting the inhibits at 80 and 90% pass rates and the reward at 85%, which would appear to be pretty loose targets, I have the potential for the client only to be scoring 61.2% of the time (multiplying the 3 together, since it’s possible that each will be blocking when the other two are both passing. A windowed squash or a percent training design give me the same effect or greater (all bands being inhibited except one reward) with a single threshold, so I can be very clear what percent of the time the client is scoring.

Percentage Feedback

I think most trainers would consider 40-50% to be pretty stringent as a reward rate and 85-95% to be pretty loose. A number of trainers have reported that they find that clients actually do better with the richer reward environments, and I have seen that in my own work with clients in a number of cases. Once again, for me it depends on the client’s response.

More impulsive, impatient clients will be bored with rates below maybe 80%–sometimes higher. More internal, lost-in-space clients generally respond better to lower feedback rates, somewhere around 40-60%, because they really can’t drift away very far before the scoring stops. In my opinion, length of training segment is also important, and the style of trainer participation is also very important. These are different for different types of training.

I generally start a session with auto thresholds and then, as they stabilize, finding the client’s baseline at the beginning of training, I switch the inhibits from auto to manual, leaving the reward bands in manual.

Define the feedback percent strictly in terms of the client. The more internal the person is, the lower reward rate I would set. The higher the anxiety level, the higher the reward rate I would set, trying to keep the client from trying too much. I actually prefer to combine continuous and contingent feedback in a design, which allows me to set a more stringent target for the contingent feedback (which only plays when all targets are met), such as the 10% I use with the chime feedback in the squish protocols, while giving the client’s brain continuous feedback that provides information via pitch and volume (or brightness of the video display).

Bored with Feedback

I’m guessing the reason you are training is because you want to get better at doing some things that you don’t do very well right now, maybe even feeling your own emotions, relating in a meaningful way with those around you, etc.

And I’m guessing that the things that are hard for you are NOT the things that are exciting and entertaining–most people don’t have trouble with those.

So it’s very possible that what you need to do is to teach your brain to do things that aren’t fun or entertaining–things like work, or learning or listening to another person or stuff like that, which may even be BORING.

Consider the possibility that you won’t train your brain to deal with routine tasks by being entertained. They might even be two different states.

I don’t know how old you are–probably not as old as me. I’m so old that I can remember many years in my life when there was no expectation that everything would be fun and entertaining. I actually learned that there were things I had to do–cooking or cleaning or doing jobs at work or school, reading and studying–sometimes even watching news on TV or driving long distances–that were, BORING (though I didn’t think of them that way.) I spent many hours of my life for many years (and I still do even now) being alone and being quiet. It gave me a great benefit to grow up and live as an adult in those times, because I learned that there are very few things that are really boring; only things that I don’t pay attention to. That freed me. It allowed me to be happy and successful in many areas of my life. I found my own way to keep interested.

Yes, I know that today those thoughts are ridiculous for many of the people with whom I work. To be still and silent in their own heads is very unpleasant for them, perhaps even impossible. They NEED to be entertained. They don’t have the ability to entertain themselves just by paying attention, by finding the interest in every task.

I have a client now who is struggling with the idea of spending 10-20 minutes per day being still and letting go of the high-adrenaline TV shows or YouTube videos or films or video games on his tablet and his smartphone. He told me 2 sessions ago that he was practicing being still for 20 minutes a day–surfing on his phone through “news” sites. He was quite surprised when I told him that wasn’t the same thing. Being still is being STILL, and it takes practice, and it’s not necessarily entertaining. But it IS empowering and freeing.

I asked him to keep track of how much time he spent on social media or surfing the net or watching TV or streaming video or music each day, and he couldn’t do it, because he does it so automatically that he doesn’t even realize it. He likes it because he can turn himself off. I asked him what he had actually produced during all those hours every day (one of his goals is to become more productive), and he couldn’t name even ONE thing that actually had any value in his performance or awareness.

When you plug in to the popular culture–never walk without an i-pod blowing songs in your ear, never wait even 30 seconds for something without checking to see who’s sending you “likes” or “tweets” or whatever–you unplug from that part of yourself which can contact the spiritual that channels within you. The “still, small voice” of the spirit never shouts–at least not until the water is already up to your neck. You grow empty inside, because you can’t make room for your own spiritual self.

Nearly everyone I see lacks that center of stillness, lacks the ability to get to their own center. They MUST have more entertainment. They are trapped by their own boredom. They think they have opinions, but their opinions are TV or YouTube opinions. They think they have feelings, but their feelings are cheap, manufactured emotions produced by media. They think they need things, but their desires nearly always go back to the ads that are a part of all that “free” entertainment they must consume every hour of every day.

Training an hour a day or two or four doesn’t fix the problem–especially if the training is all about being entertained.

Use a music/video feedback design and set up a playlist of fractal zoom videos (get some good ones at ericbigas.com). Put on headphones and listen to the music and watch the video. Boring as hell! But allow yourself to get still, as much as you can, practice doing breathing exercises and paying attention to your breaths. Practice the breathing for 3 minutes, counting the breaths, 2 or 3 or 5 times a day. Let yourself find that still center and get comfortable staying there for longer times. Get used to being “bored” until you recognize that people are bored because they are boring. There is no “them” within themselves. They become cultural consumption robots for whom “friends” are people you’ve never met on a social media list, for whom, “like” is an opinion, and stillness in their own center is a thing to be avoided at all costs.

Four-Channel or More Training

I’m not aware of any data comparing multi-channel with 2-channel options. In areas other than sum-channel options (synchrony, squashes, squishes, etc.) it becomes rather complicated to set up 4-channel protocols without ending up with a large number of inhibit and reward bands.

One of the benefits of 4-channel over 2-channel would be that you can cover a lot of real estate in the brain. For example, in a brain with excessive fast activity on the right hemisphere, instead of training F4 and C4 in one protocol and then repeating the protocol in T4 and P4, you could train pretty much the whole right hemisphere to do the same thing at the same time, saving training time and perhaps making the effect more powerful.

There is, in the brain-trainer package, a 4-channel synchrony design that uses coherence and phase difference values among multiple relationships in the 4 sites.

Frequency of Training

There are reasons why I would not personally train every day. One reason is that the effects of a training session may be seen anywhere from immediately during/after the session to 12-24 hours later. So even in the beginning, training every day tends to make if difficult to recognize connections between one training’s effects and another’s. With a day break between sessions, the client can attend to what happened during/after the session and that day, then what happened during sleep and the next day. Training every day would be like going to a wine tasting where you have to taste the wines one right after the other.

Since we are training for changes in the client, the way I decide when training is “done” is by stretching out the inter-session period as we go through the cycles. Doing the first cycle, if I can train 5 sessions in 5 days, I would do it, including 3 HEG sessions. During the 2nd cycle, I would train every other day–completing the cycle in two weeks instead of one–and begin identifying and measuring the changes starting to happen. In the third cycle, I often leave 2 days between sessions. If the client is showing stability in the change he is experiencing, so it lasts between sessions, we may stop at 15 sessions. Often we will do another 5–sometimes stretching them out over 3-4 weeks–sometimes just shifting to alpha theta training.

Gender-Related Differences

Everything I’ve ever seen about brain function–I don’t track anatomy and geography–shows little or no gender difference. All of the work done on alpha and beta symmetry has obviously been done with men and women, and everything backs up the beta-stronger-left, alpha-stronger-right findings for emotional stability.

Handedness and Training

Way back in the 90s the Othmers did a nice little study where they took a group of children and measured everything they could think measure on them prior to training, then measured again post training. It between they simply trained C3/A1 and C4/A2 per their (at that time) standard ADHD protocol.

One of the things that struck them in the pre data was that, while in the general population about 92% are right-handed, among the ADHD kids, about 50% were right-handed, about 30% were lefties and 20% were mixed dominant. Dominance is one of the relatively early decisions a brain makes as it matures, since it allows the brain to divide functions and work more efficiently. ADHD is essentially a label for delayed brain maturation (which is why people so often say, “he acts younger than his age.”)

Following the training, the post findings showed, as I recall, that around 85% of the same group were now righties and the other 15% were lefties. None were still mixed dominant. In other words, up to 15% of the left-handers had become right-handers with no other intervention and all the brains had “picked a side” to be dominant for language which allowed them to become better organized, more efficient and more mature–less ADHD. That was without other exercises such as BrainGym or Interactive Metronome, though those systems can be helpful as well.

Headphones

You can’t use headphones with any kind of electrical circuitry, volume controls, noise-canceling ability, etc. Use plain headphones or earbuds. If you do an internet search on ear clip headphones or clip on headphones, there are many inexpensive brands that do not interfere with electrodes on the scalp the way standard headphones may.

Hemispheric Dominance

If you are right-handed, as is roughly 92% of the population, your left hemisphere is dominant for language; right for music and emotional response. If you are left-handed, there is about an 85% chance that you’ll be the same as the righties. Roughly 1.2% of the population has brains that have organized to use the right hemisphere for language (for which it’s not as well suited) and the left for music and mood (also for which it’s not as well suited).

There are tests of dominance of sight, dominance of hearing, various tests crossing arms and folding hands, etc. that purport to tell you which of what is dominant for whatever, but people usually end up pretty split on those. There was a very good test of asking a person to (as I recall) remember something, or count backward by sevens or something where you would watch to see if the person looked up and to the left or the right that I used to use.

Looking at the EEG, if you have a lefty to train, you might look at the Theta/Beta Ratio section on the Analyze page of the TQ8. You can see if the theta/beta ratio is lower (or more in the white range) at C3 or C4, and which one best activates at task. That can be helpful in determining at least which side is working harder on a language task when one is assigned. If it really becomes a training issue, which it has only twice in my career as a trainer, try reversing the training for cognitive performance and see it the response improves. If you have been training up beta at C3 and SMR at C4, reversing those may give you an idea if you should train that way. You can look at the same things in the frontal and parietal lobes. If you find the right side activating more strongly in all of them, that would be a stronger indication of right-dominance for cognitive tasks.

One of the interesting unanswered questions in neurofeedback for me is whether reversal for language has any effect on alpha and beta reversals and their relation to mood. As far as I have seen, it does not, but then, as I wrote above, I haven’t had much experience with left-handers reversed for language.

Head Injury and Dominance

If someone has a head injury of whatever sort, then the issue of hemispheric dominance would drop way down in importance as I developed a training plan for that brain. Obviously if you chop off a right-hander’s right hand, he probably won’t be a right-hander any more. The issues of hemispheric dominance are important absent more foundational issues.

Mixed/Incomplete Dominance

Remember also that there are several different conditions related to dominance. There is clear left dominance related to language tasks, which is by far the most common condition. There is clear right dominance related to language tasks, which is fairly rare and seems to be limited to clear left-handed people. There is also mixed or cross or incomplete dominance. This is a lack of complete organization in the brain, and it shows up in a high percentage of people with Filtering problems. The client will tend to do some things left-handed and others right-handed. It may or may not be clear in the EEG in various areas. Some people test for multiple indicators of dominance (eye, hand, finger, arm, foot, etc.).

Eye-Movement Test for Dominance

One of my favorites of these tests is the “conjugate lateral eye-movement” test, which is also neurologically based.

Sit facing the client and give him/her a moderately challenging mental math problem to perform (don’t make eye contact). Watch for movement of the eyes, which should go either left or right, when the client is performing the task. Repeat several times (I like to do this during the parietal assessment challenge task). If the eyes consistently move to the right, the client is using left hemisphere for math calculation. If the eyes move consistently to the left, the client is using the right hemisphere. There is a very high correlation between dominant hemisphere for calculation and for language. Some clients shift back and forth, which indicates mixed or incomplete dominance. My favorite client of all time in this test went left..then went right..then up…then rolled her eyes in a complete circle. I have no idea what that meant.

It is important not to make the task “impossibly” difficult in the client’s mind, or you’ll get no movement at all.

Impedances

The higher the impedance–the resistance to passage of the signal between the scalp and the electrode metal–the poorer your signal will be and the more likely you are to have electromagnetic fields enter artifact into the signal. High impedances are usually the result of poor connections. If you have high impedances, redo your connections.

60 Hz is always and everywhere present in any US environment.

Think of the old analog radios that you had to tune in by turning the tuning dial. If you were dead on the center of the station you would get a stronger signal of music (back in the blessed days before talk radio) and little or no static/noise. If you were a little off the center, you’d start to get static, and the further off you were, the worse it would become until you couldn’t hear the programming any more.

The hookup is your tuning dial. If you could get absolute zero impedance and balanced impedances among all site pairs, you’d pick up your tiny little EEG signal loud and clear. The higher the impedance–that is, the greater resistance there is between the scalp and the metal of the electrode–the less effectively the EEG signal can pass and the more easily the “noise” of 60 Hz can enter the conductive paste and electrode. Any time you see 60 Hz high at one site but not another, it’s almost certainly a poor connection–poor prepping (remember you prep “long, not hard”), too much hair between the electrode and scalp or too little paste. Re-prepping and resetting the electrode will usually resolve the problem.

If you have high 60 Hz (that is, equal to or higher than the tallest other signals on the power spectrum), especially on both sides, this can indicate a problem with the power. Using an ungrounded outlet (pretty rare in the US, but very common here in Brazil) or sometimes using an ungrounded power supply for a laptop (2 prong plug instead of 3-prong) can be a problem. If using a laptop, unplugging the power supply FROM THE WALL–not just from the computer–can often result in a big drop in 60 Hz if that’s the problem.

Watching the oscilloscope is also very helpful. A good EEG signal is a thin line running along a fairly stable baseline (not “wandering” all over the screen). Most importantly, it is “organic”. The wave widths (frequencies) vary, getting wider and narrower, and the wave heights (amplitudes) also vary. When you have 60 Hz interference, you’ll notice that the wave form suddenly becomes very regular: It is very fast (you can count the number of wave tops in a division on the display and calculate the frequency: it will be 60). Most important, it is unvariable–mechanical rather than organic–with every wave the same width and roughly the same height.

Using a Gauss Meter

You may pick up a Gauss meter ($36 at http://www.lessemf.com/gaussmaster.html) and see what the levels are inside where you’ll be doing your training. You’ll probably find that the field produced by the transformer on the AC adaptor for your computer are much larger than those from other sources (since the strength of the signal falls at a rate that is the square of the distance (my recollection of physics may be a bit rusty). (You can also use it to detect ghosts and other paranormal entities per some websites).

Even better, take your laptop and an amp and see what kind of signal you get before you rent the space. I’ve only seen three situations where there was a serious environmental effect that couldn’t be resolved. One, in Zurich, was an office directly beneath a police station with major communication equipment in it (transmitting), one was in Sao Paulo where an office was less than a block from a transmission tower for a television station. The third was in an office in California–and we never did figure out what was causing that–but in all three cases doing neurofeedback was not feasible.

Linking Training Sites

Symmetry, synchrony/coherence and assessments should always be linked because they are training comparisons or relationships between the two channels. Comparing each channel against a separate reference allows error to creep into the measurements by adding another variable (the signal at the reference) to change the apparent relationship.

The jumper/linked references allow you to combine the signals from the two reference sites, and compares each of the actives against exactly the same value. I guess you could say that “zeroes out” the references, but I’d say it just equalizes them. They’re still subtracted from the active sites to give you the signal.

Some guidelines:

If you are using a COMMON reference (e.g. F3/A1/g/C3/A1–both channels using A1): YES, link.

If you are using LINKED reference for “comparative” training (e.g. coherence/synchrony, symmetry, assessment): YES, link.

If you are doing “summed” training (squish, squash, windowed squash), use it if you wish, not if you don’t. Doesn’t matter.

Otherwise use independent references, meaning that the link button should NOT be on.

Muscle Tension

Some clients I used to run into in Atlanta would have excessive levels of muscle tension that was “invisible”. I could never find anything tense, yet they produced very high EMG levels no matter what they did. Usually training them, SMR was a good option, with whatever signal we could get, would slowly bring it down within a session and the “interference” would go away. It would take a number of sessions for the release to last.

I’ve only seen one or two people with global coherences even in the 80s. In both cases there was severe tension (scalp tension is harder to see). What causes most signals to be coherent is that they are coming from the same source.

Not Getting Results

Asking about signs that neurofeedback is not working or is having negative effects is perfectly valid and answerable. It’s not working if the desired changes aren’t starting to happen within about 10 sessions or less. I know lots of folks (with knowledge bases 14 feet wide and 3/8 inch deep) who keep slogging along at the client’s expense for 30, 40, 50 or more sessions doing the same thing religiously and getting the same results–none. You can tell brain training is having negative effects in the same way: by looking at the client. If the client gets irritable or foggier or has pain or headaches or can’t sleep when he could before or…well, you get the idea…after a session, you take notice. First you would wonder, is this really a thing that hasn’t happened often before. If a kid who has headaches 6-8 times a month has a headache after a session, did the training cause it? Unlikely. Still, you want to know it and factor it into your planning. If a kid who is sweet and quiet and pliable kicks the dog and bites his sister in the several hours after a session, then you’d probably look at changing your approach.

Reactions to Training

Physical Reactions

For very stressed people, tingling in hands and feet as a reaction to neurofeedback can be a result of shifting into parasympathetic mode, so the blood gets back out to the extremities. Whole body tingling might just be a person actually being in touch enough with his sensory inputs to actually be aware of himself as a sensing being. Wild guess.

Reaction vs Rebound

The rebound effect is an autonomic phenomenon.

When a person has high levels of autonomic tone–they have a tendency to be stuck in sympathetic (fight-or-flight) mode, the brain and body believe they are in an emergency situation. That often appears as high levels of fast-wave activity, often in the back of the head and/or on the right hemisphere. It is fairly common for some brains to respond to this very demanding and tiring state by learning to produce alpha (often slow alpha) as a kind of self-medication. In the alpha state, you can numb out those feelings of fear and anxiety. When someone tells your brain to stop doing that, it’s no big surprise that the brain responds by suddenly revealing the underlying emotions being covered up by the alpha.

Strictly speaking, that’s a reaction, not a rebound. Rebounds (like panic attacks, migraines, irritable bowel, etc.) are physiological responses. When the brain is convinced that the world is a dangerous place, it believes it must maintain a high level of vigilance and readiness. That sympathetic state draws energy from the parasympathetic functions of body maintenance, including sleep, digestions, circulation, blood pressure, heart-rate, breathing, etc. When a person who is highly self-stressing is suddenly led to relax–by training or a reduction in some external event one finds stressing (e.g. end of work, completing the budget, etc.) the brain shifts back to parasympathetic (rest and digest) and stops being vigilant. For a while. But in many cases, the brain will suddenly “realize” that the security guards are all taking a nap at the same time and in a panic “rebound” into sympathetic mode. Suddenly anxiety explodes or the heart begins racing or you can’t catch your breath, but there is no “reason” identifiable. That’s a sympathetic rebound (panic attack in those who experience anxiety physically).

A parasympathetic rebound happens when the effects of releasing the emergency response cause an excessive physical change. When we are in fight-or-flight, commonly blood is drawn out of the extremities of the body into its center to be ready to go to war. Hands and feet may get cold. Blood is released from the brain (no need to think, we’re just in reactive mode). When suddenly the emergency mode ends, blood can rush back to the extremities (tingling hands or feet) or to the brain. In the latter case, if the brain doesn’t have a robust system for handling all that blood, it’s like 5 o’clock traffic hitting all at once and there’s a traffic jam. The result is a sense of pressure and throbbing (the heart trying to push blood into an area that has no room for more) which we call a migraine. Or a sudden burst of activity in the digestive system out of sync with normal digestive activity (irritable bowel.)

The key to avoiding these is often to focus on training the underlying anxiety patterns while at the same time slowly working to reduce autonomic tone.

Session Timing and Length

When we set up designs, we don’t know if the trainer will be working in sessions that combine HEG and EEG, or doing EEG only, doing one exercise per session or three. The choice of training time is usually based on the degree of activation involved.

If you are training to speed up brain activity–increase energy expenditure–then most of those protocols will be run for shorter periods. If I have a really slow brain, I may train for as little as 1-2 minutes per segment, give the client time to “catch his breath” between segments. So, I might do 5 segments of 2 minutes. In the same way, if you start doing aerobics with someone seriously out of shape, you don’t ask him to start running 5 miles.

For middle speeds, like alpha or SMR, I will often use a training segment of 5 minutes–time enough for the client to get into the stillness, but not so long that his brain can’t sustain it. So I might do 2 segments of 5 minutes each.

For deeper states, I often use 10 or 20 minutes as a training period, so the client has time to get into that deeper place.

Each trainer needs to select how long to train each segment (usually based on how many EEG training minutes are feasible in a session and the number of protocols/exercises to be trained).

For overall training time, I usually figure 15-20 minutes for HEG and ten more for cap placement and removal, which leaves me 30 minutes for EEG. If I’m doing three protocols, that’s eight or nine minutes per protocol. I like to do shorter exercise sets like that, at least in the beginning. After that, we may decide that one of the protocols is not particularly useful and drop it. Or we may find something that works really well and include it in other blocks. I often do six minutes of BAL4C RH and then another six of C3/C4 SMR% together.

As for EO and EC, I try half the neurofeedback training time one way and half the other to see how the response differs. After a few trials, we might switch to doing the whole block with one or the other.

Timing of Sessions

In my work with clients, I have generally used the analogy of working at the gym. If you go once a week, you may feel better after the workout, but you are unlikely to produce any long-term changes. On the other hand, working out every day may not give a lot faster changes. I believe two-four times a week is ideal. Training the brain, like training the body, involves changing an energy set point. That takes time and consistency. I like taking a day off between sessions to see how well the changes hold from session to session.

Frequency of Sessions

I don’t know of any specific research on frequency of sessions. I suspect it would be a pretty individual response. In my experience there was often a benefit (especially with kids) to an intensive beginning to training (3X/week), but I also strongly believe that the systemic change that occurs with most training requires a period of time as well.

In Atlanta we often had folks who came a distance for training and tried to mass 2-4 sessions around a weekend, and that generally seemed to work as well as spreading them out during a week, but I don’t recall that doing more frequent sessions resulted in shorter training (certainly in terms of sessions, but to some extent also in terms of duration of the training process.

I suspect that, as with for example weight training, there is a benefit to inter-session resting. Certainly, that has been found by Hershel Toomim, who has studied a number of training frequencies and found that, in HEG at least, every four days gets the same results as more frequent sessions.

A general rule would be if you are training to calm the brain, more frequent could be helpful; to activate it, you can train more frequently but it is still likely to take some time to get the change to occur and stabilize.

Training Too Often

Frequency of training depends on the client. The main issue would likely be burnout. I generally suggest that people train every other day, so they have enough time to see changes and see how long they last before fading between sessions. I suppose that with certain types of problems more intensive training could be fine, but it’s usually a good idea to take training vacations from time to time if you are going to do intensive training over a period of time.

As a general rule, I would say that 30 sessions in 15 days probably do not take a client as far as 30 in 60 days, but I think that might be very individual, and it may even relate to the type of problem and training. Certainly with alpha or even alpha/theta training, there may be an immersion benefit–just as meditators go on meditation retreats that absolutely overwhelm them in the meditative practice. However, if we are trying to speed up the brain, then there is a physiological/metabolic change that must take place (in my opinion). There the analogy would be like working out with weights. There is a re-charge period required for the body to change.

That said, I think that maybe doing 10 sessions in 5 days can have a pretty positive effect. I just never found that doing 40 in 20 days had the same effect as doing 40 in 3 months. Other things have to change as well.

Skull Thickness

I’ve heard from a number of folks who are experts in EEG that the single factor that accounts for about 85% of overall differences in absolute EEG amplitudes is thickness of the skull. The reality is that some people just have thick skulls.

Training Specific Bands

I’m careful about trying to train down just a narrow frequency band (i.e. just delta). It’s very possible to reduce delta and increase theta or even (if there is dissociation involved) high beta. Squashes and windowed squashes are a good alternative in that they allow you to put a ceiling on a wide range of frequencies without necessarily training to increase anything. When the brain reduces amplitudes, it is activating its control circuits, which is usually what precedes improved function.

I also often find that using wider-band filters (for example, 19-38 Hz rather than 19-23 Hz) not only allows you to set your filters to be more accurate AND faster, it also blocks activity from shifting bands. If you have a very fast brain, and you decide to train down 19-23 Hz, it’s not completely unexpected that the brain might move to a nearby frequency that is also fast. That’s where it’s most comfortable. But if you use a squish, training down two sites at the same time with summed amplitudes and a band that covers all the less useful fast frequencies, then the options are limited. Either the brain improves control circuits on those neurons and they simply stop firing, or it shifts to alpha or some other frequency.

Any time you use a frequency down/frequency up protocol, in most cases the brain will do one or the other. If you succeed, for example, in reducing theta amplitudes, you will usually end up reducing beta amplitudes as well–even if you are rewarding them. Or if you succeed in increasing beta amplitudes, you’ll probably increase theta as well, even if you are inhibiting.

When to Finish Training

Usually by around 3 cycles through the blocks of training, you should be beginning to notice that changes are becoming more stable–not fading after a session. At that point I usually start stretching out the sessions. If you’ve been doing them 4 times a week, try dropping to 2; if 2 times a week, drop to 1. The idea is to verify that you are not regressing between sessions as you increase the period between them. If that turns out to be true, then decrease session frequency again. Eventually I like to see that even with 2 weeks between sessions, the benefits of training are holding–that indicates that a new homeostasis has been formed.

If you live an active life, you may need to join a gym or do some exercise to get yourself in shape, but you shouldn’t need to keep working out constantly. Using your body in daily life will keep you in shape. Most of the people I’ve trained have made a stable change in their brain function and been able to stop training. Unless you bang your head against a wall, or start using substances regularly, or move to Bali and lie under a palm tree and stare at clouds all day long, chances are your brain will stay strong and continue to develop without ongoing training.

Some clients prefer one or a few protocols and will choose to do a kind of Level 2 training–maybe 5-10 sessions of alpha theta 1-2 times a week, or sessions of SMR or working with the Default-Mode Network or Alpha/Gamma Synchrony. Those are enjoyable and open us up to ourselves in positive ways. As you get older, you may find that you need to do some Alpha Peak Up training or some HEG (at least I do) maybe twice a year for 8-12 sessions, just to hone the sharpness of the blade.

Unless you believe that there is a normal brain or a perfect brain that you seek to achieve, doing more assessments and constant training is a bit obsessive. I would take at least 6 months off after I finish training to let the brain stabilize in its new place. Most of the people with whom we did 1-year follow-ups in Atlanta reported that they had experienced greater changes in the 6 months AFTER they finished training even than they had during the active training period. Your brain is to be used, like the rest of your body. Yes, you can decide to become an Arnold Schwarzenegger and make your body your life, but I’m guessing you’ll end up finding lots of better things to do.